When creativity and curiosity collide, the end result can be something really cool! That’s just one of the many takeaways for students from a special Monday middle school assembly on January 30, when Andrew Innes, creator of the successful card game Anomia, spoke about his journey into the world of game design.

The term “Anomia” is defined as the inability to name objects or to recognize the written or spoken names of objects. For those familiar with the game, this is a common occurrence and one that makes for boisterous and chaotic fun. The game has been hugely successful, having sold 400,000 copies in 17 countries and been translated into 10 different languages.

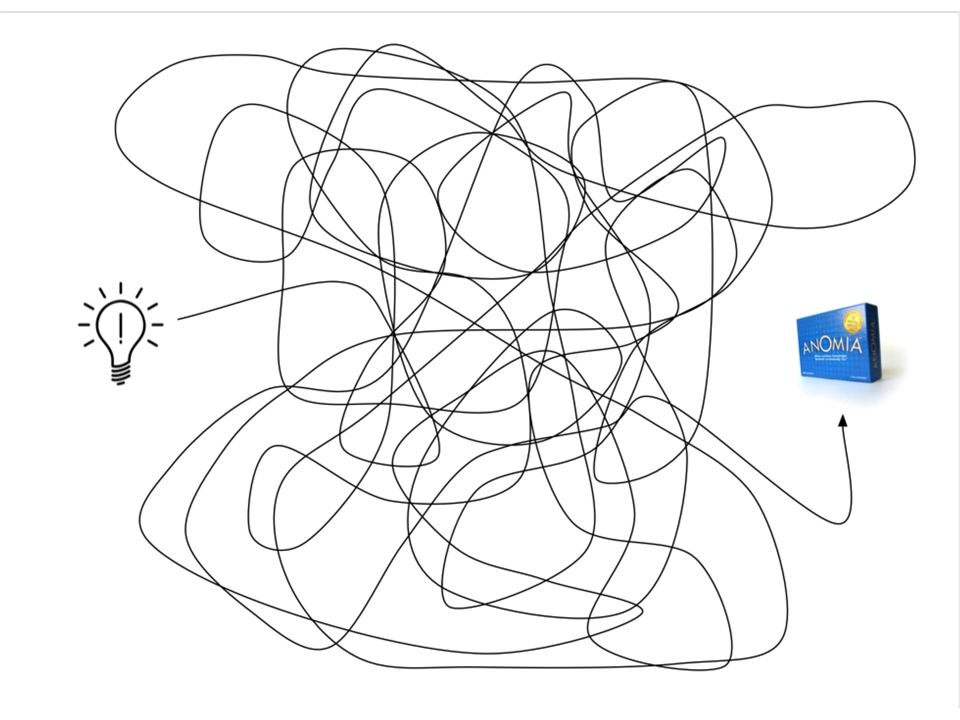

Tracking its development, Innes told students that he was 12 when he came up with the idea for the game but it wasn’t until his forties that his vision became reality. And, it wasn’t a straight line from idea to finished product, he noted. From musician to small business employee, to working in publishing, to becoming an app designer and now game creator, he described how he gathered experiences, communities, and skills along the way that helped him become who he is today. He told students, “You learn from all the different experiences you have in life, and they don’t have to all be going in the same direction or in a straight line for you to achieve fulfillment, happiness, and success,” certainly a valuable lesson for all.

Middle school students also got a lesson from Innes in the creative process. He talked about how he took his original game idea, created a prototype, tested it with communities of game players, observed their reactions, refined the design with more prototyping, tested it again, and ultimately came up with a finished product for manufacturing. He stressed the importance of listening, watching, and learning during the testing phase. “You have to learn to be silent,” he explained. “You also have to be willing to seek out help from others to fill in the gaps where you may be deficient.” For him, that help came in the way of graphic design skills and funding. Innes sought some help from a friend in drawing the cards and borrowed money from family to produce his first 2,500 units, a loan he said he promptly repaid.

With the success of the game, Innes has identified ways to expand and branch out into new subject areas while still maintaining the original structure and rules. When asked why he thinks it’s been so successful, he said, “It’s easy to play; you don’t need to spend a lot of time reading rules; people can be silly and smart at the same time; it’s boisterous, chaotic, and makes you laugh.” In the digital world of today, it’s refreshing to have a game where batteries and screens are not required, one of many good lessons for DCD middle schoolers on this Monday afternoon!