After graduating from DCD, Nobles, and Harvard, Henry Singer ’70 headed to the business school at Yale University, a traditional trajectory for a man of his background and education. As he tells the story, he left after an hour, and at 27 years old, started over, in a new profession to which he has passionately dedicated himself over the years since that fateful decision—public service.

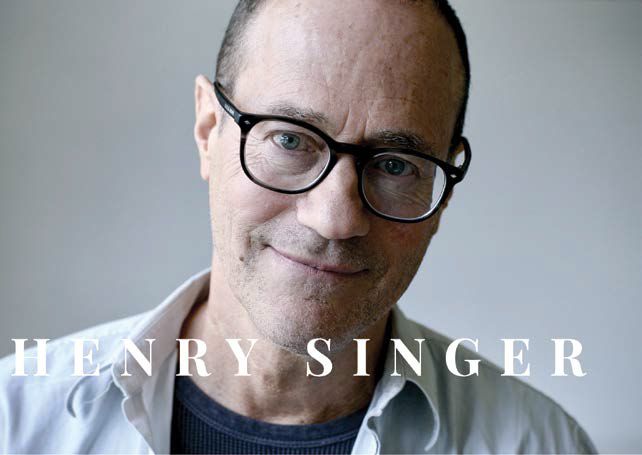

Henry, now one of the most critically acclaimed filmmakers in Britain, is the founder of Sandpaper Films, a company that makes films and series for the UK and international broadcasters known for their powerful storytelling. He has won or been nominated for every major British documentary award, including the BAFTA, Royal Television Society, and Grierson, as well as an international Emmy.

“One of the reasons I went into filmmaking was public service. It was part of the ethos of DCD and Nobles, and it was certainly how my mother brought me up,” he said.

His curiosity about people is another key reason he cites for going into filmmaking. “It’s a wonderful way to go through life,” he said. “You get to meet a succession of people and spend hours just asking them questions on first meeting.”

“I take on dark subjects,” he says, as he lists some the more notable ones: “The Falling Man,” about the “jumpers,” in particular, one man falling from the World Trade Center on 9/11, another film about the seven days following the death of Diana in the film “Seven Days,” “Betrayed Girls” about a childhood-abuse scandal, and “Baby P,” about an 18-month-old toddler who was beaten to death.

This spring, before everything closed up in Boston due to Covid-19, Henry gave a talk at the Boston College Center for Human Rights on his latest film “The Trial of Ratko Mladic.” Mladic was one of the most infamous figures of the Bosnian war of the 1990s, known for the merciless siege of Sarajevo, in which 15,000 people were killed or wounded, and the murder of over 7,000 Muslim men and boys in Srebrenica in 1995— widely considered the worst crimes in Europe since World War II. Filmed over five years, the documentary covers all aspects of the trial, going behind the scenes with prosecution and defense lawyers and witnesses from both sides.

“This is an incredibly important film,” Henry said, “especially given the current climate, with leaders like Assad in Syria and so many others around the world acting with impunity. The trial was a moment in history when the world got together to bring to account a terrible monster.” Mladic was convicted of genocide and crimes against humanity by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia on November 22, 2017.

“His trial was a huge world event that was not getting any attention. My partner and co-director Rob decided to direct a film on it and worked on it for years, largely for free, while individually making other films to pay rent. It was a labor of love, but I’m glad we made it,” he said.

“In the midst of having tiny children and being an incredibly old father, making two films at that time was complete lunacy, but I lived to tell the tale,” he joked. At 62, married, with two young children, Mila, 7, and Max 3, Henry calls himself the “quintessential Peter Pan.” “My advice to anybody is to have children when you’re a good deal younger.”

Luckily for his family, he doesn’t take his work home with him. “I have quite a sunny personality,” he explained. “I try to stuff as much fun as possible into my life. I can go into the darkness and come out of it and be largely untroubled by it, not that I don’t have empathy. I have enormous empathy. And, I wouldn’t do it if I couldn’t handle it.”

I’m not unfeeling,” he explained, “it’s just that you have a job to do, and you want to do really good work around important subjects and keep your eyes on the prize. It’s probably what war photographers have to do in documenting the horrors of war. It’s their mission. People like that have enormous empathy, but while they’re doing it, they’re really doing it; they’ve got to deliver the goods.”

“If you’re trying to make films that are a service, they tend to be about social injustice and most of them are about death. We as a species do awful things to each other. These are the kinds of stories that need to be brought in to light. What’s driving me is to do work that is of public service.”

“What keeps you going is that you’re doing useful important work. These feel like darker times. It’s more important to shine the light at times like these. People need to know that there are alternative ways of being and alternative value systems. That does keep you going.”

Having received so many accolades over the years, Henry said the award that means the most is the one he received for the Mladic film, the Grierson, considered the highest non-fiction documentary film award. “What felt really good was that we were up against some excellent films, including “Knock Down the House,” the story of four women of color, including AOC, following their campaign in 2016, which won at Sundance and sold for enormous money to Netflix. It was the caliber of competition that made the award gratifying, not because it took five years to make.”

He explained the public service genre of filmmaking has moved from being non-commercial public service to becoming more entertainment. Mladic was an “old-fashioned, classic, public service film,” he said. “Netflix would never commission a film like that. You’re not likely to come home on a Friday night and watch a war trial, a film about genocide. It’s not light entertainment viewing. It was gratifying that a film like ours was recognized.”

Henry had to raise 900,000 pounds and spend a lot of time fundraising, adding to the stress of making two films at a time, and asked himself many times, “How did I get into this?”

As to what’s next for him, he said, “I’m hoping to win one gold-medal position. I’m developing plans to grow my little company and working to put together a slate of films to sell to BBC, Amazon, Netflix. I’m raising money for a climate-crisis film that will cover what I believe is the biggest existential threat we’re facing right now.”